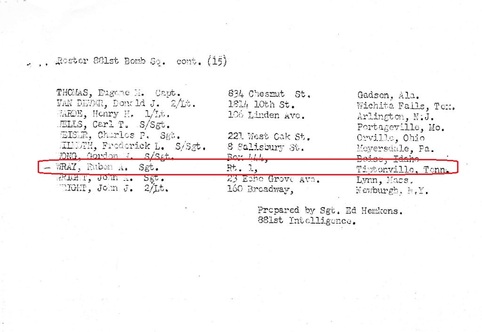

Uncle Bob

Back Row, 11th from Right to Left

Below is a downloadable file of all of the 500th Bomb Group SSDI Records - (courtesy Ed Lawson)

| master_file_a-z_3-21-12.docx | |

| File Size: | 791 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

Dick Sheil and I have just completed checking the SSDI records of the men of the 500th (about 3700). We found death records of what we think are the right men for about 50%, there is another 25% that we cannot tell because there

are several/many men with the same name. The last 25% are either still living or there are no records.

For enlisted air crew, I think the age average was about 20 with a fairly narrow range. For officers, the average age was a bit older, perhaps, 23-25. There was a greater range for officers.

(Ed Lawson responding to crew ages inquiry)

are several/many men with the same name. The last 25% are either still living or there are no records.

For enlisted air crew, I think the age average was about 20 with a fairly narrow range. For officers, the average age was a bit older, perhaps, 23-25. There was a greater range for officers.

(Ed Lawson responding to crew ages inquiry)

Images of typical medals awarded...

Below are 3 document images of the Distinguished Unit Citation signed 13 Nov 45. for action by the 500th Bomb Group for the bombing raid on Nagoya on 23 Jan 45.

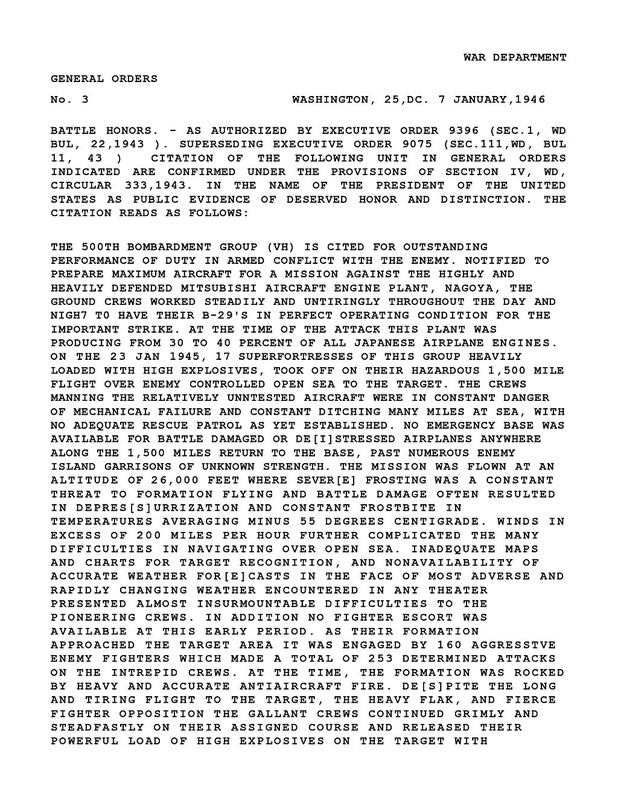

The below 2 document images are the Presidential Unit Citation 7Jan 46.

For action by the 500th Bomb Group for the bombing raid on Nagoya on 23 Jan 45.

For action by the 500th Bomb Group for the bombing raid on Nagoya on 23 Jan 45.

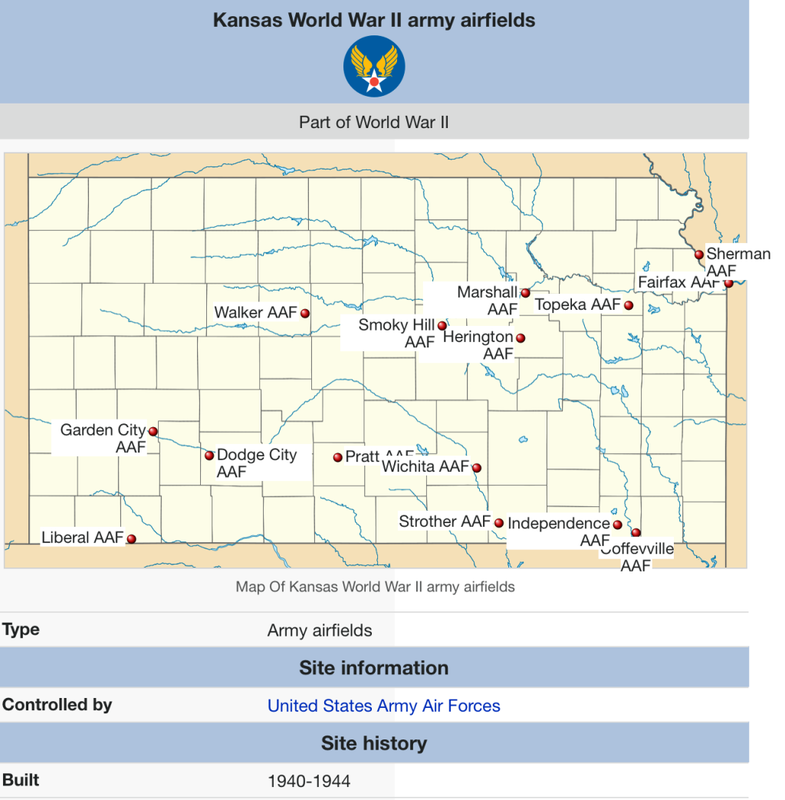

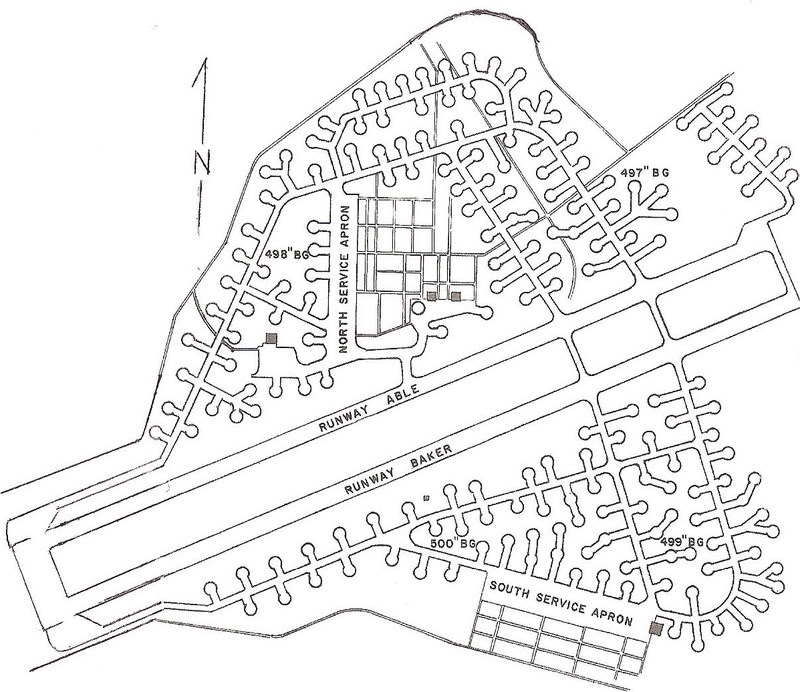

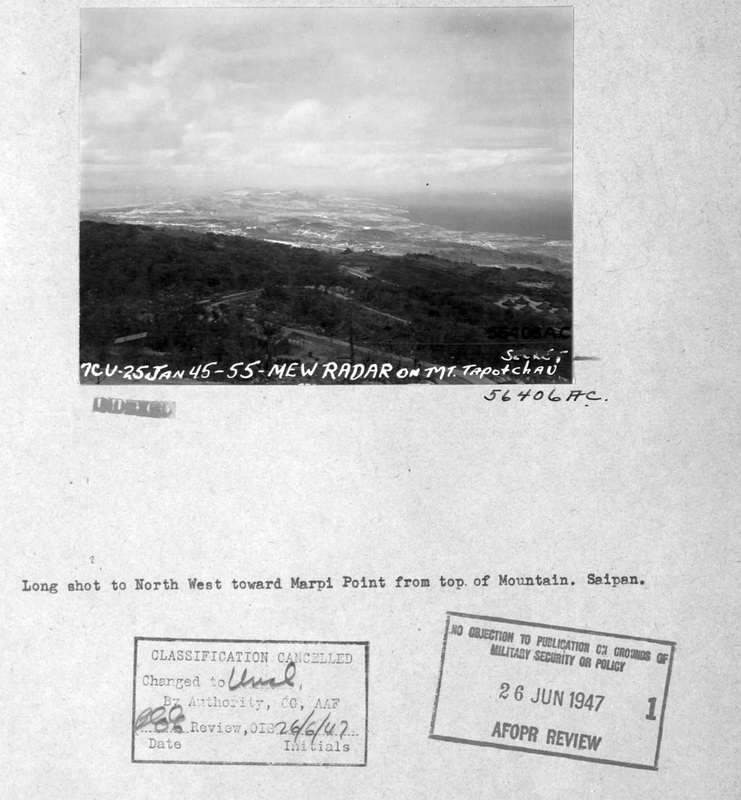

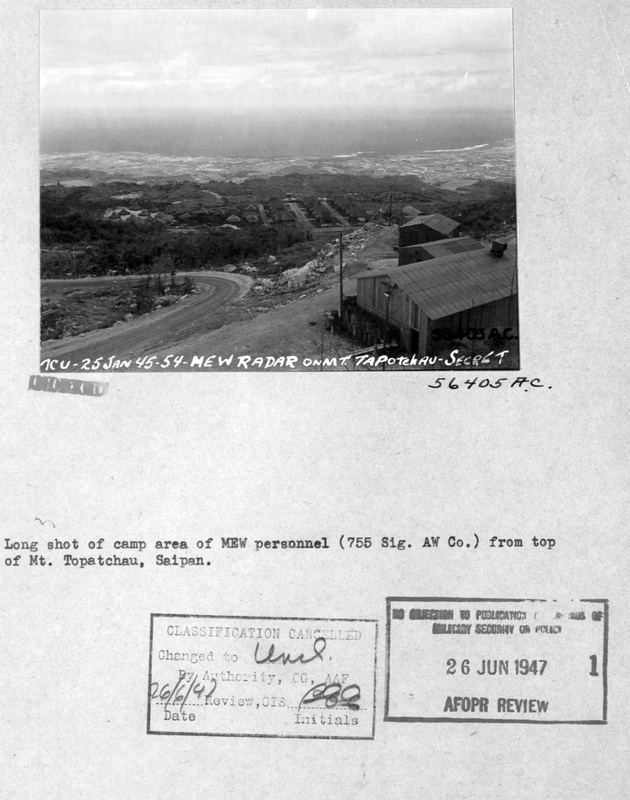

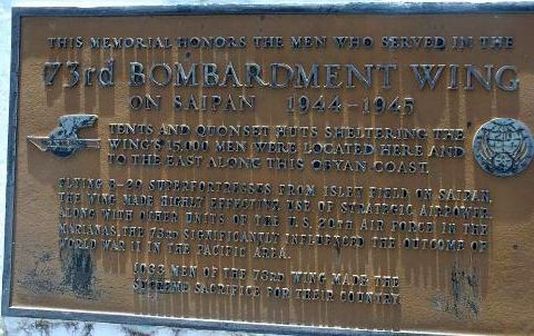

UNIT COMPOSITION:

The 73rd Bomb Wing on Saipan was composed of four very-heavy Bomb Groups, the 497th, the 498th, the 499th,

and the 500th. There were three squadrons in each group.

Additionally, the 313th Bomb Wing was assigned at North Field, Tinian, and the 58th Bomb Wing from the CBI was assigned to West Field, Tinian. The 314th and 315th Bomb Wings were both assigned to airfields on Guam.

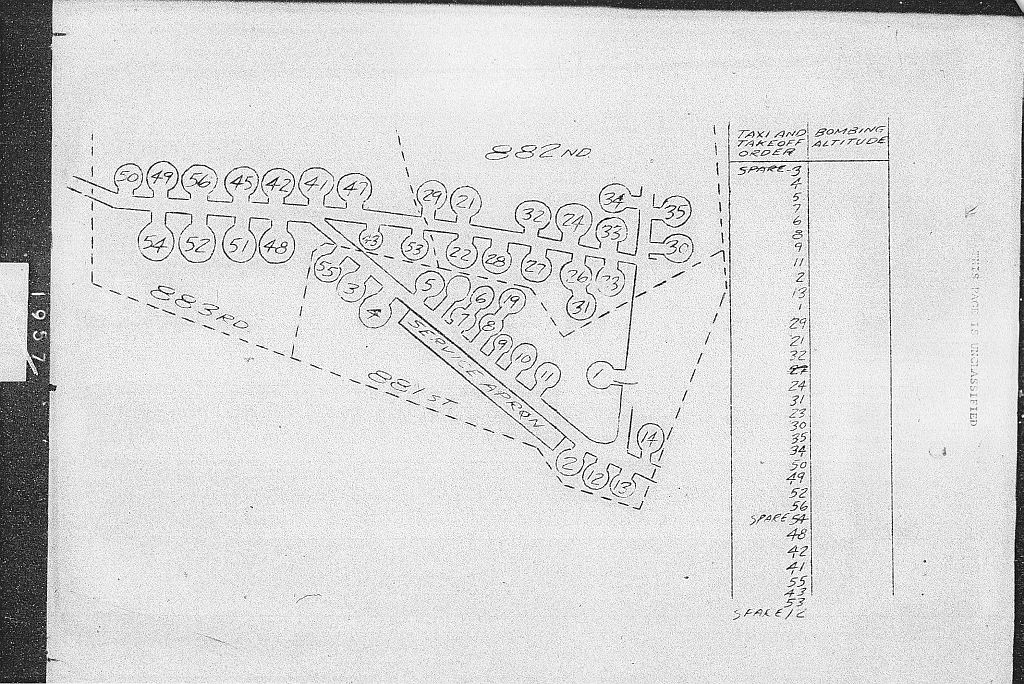

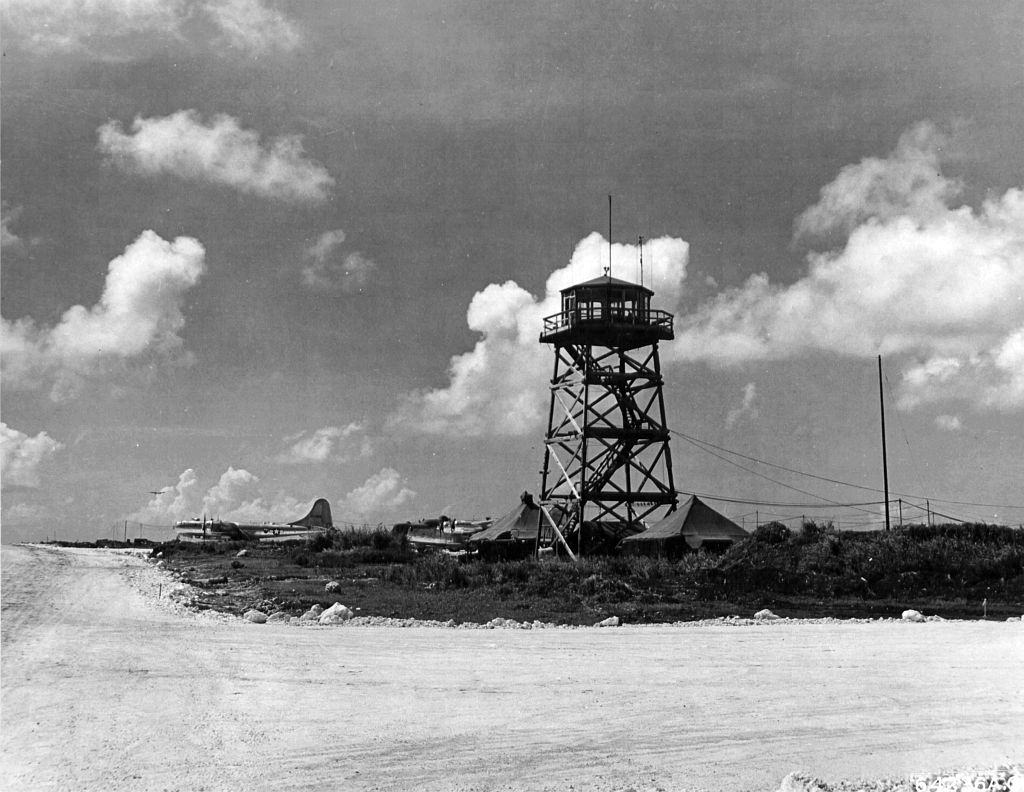

RUNWAYS:

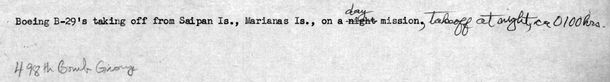

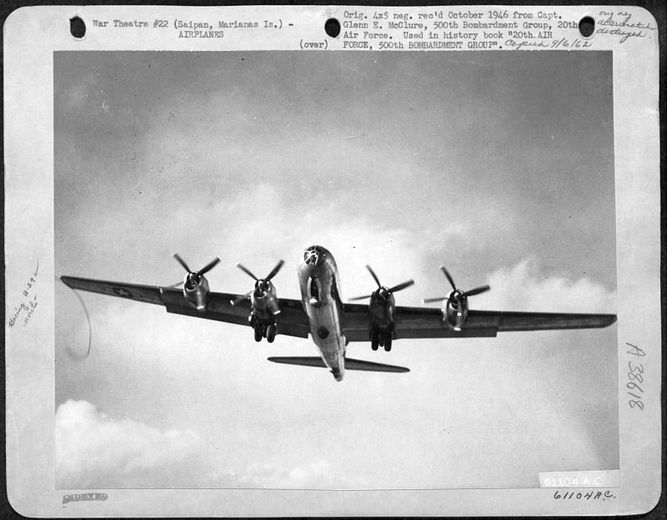

Eventually, Saipan had two parallel 8800 foot runways to launch their B-29s. A flagman would dispatch the planes from his assigned runway at appoximately one minute intervals, but staggered by 30 seconds from the other runway.

Thus, Runway A would dispatch a plane, and 30 seconds later Runway B would dispatch another plane, and this went on until all planes were airborne. If done properly, and there were no emergencies or aborted takeoffs, a plane would be lifting off from Saipan every 30 seconds.

PREFLIGHT:

Crew Inspection: Each member inspected to ensure he had his particular assigned equipment for his job, i.e. radar, navigator charts, etc. Plus his parachute, MaeWest, flak and survival gear.

Aircraft Inspection: A/C and Pilot checked all aspects of the plane, and each individual checked his particular area. Especially the gunners.

Props: The crew had to pull the props through at least four complete rotations to transfer oil from the

lower engine cylinders to the upper cylinders. This prevented cylinder damage due to oil seeping out of the top cylinder to the lower ones when the engines were not run.

ENGINE START UP:

Usually started from outboard left (#1) across to outboard (#4), but not manditory as we understand it.

A ground crew member always stood by each engine with a fire extinguisher when started, in case a fire broke

out in that engine. One ex-B29er told us if that occured, their rule of thumb was to shut everything down and

get away from that airplane.

PUTT-PUTT:

This little gasoline engine was usually started by the tail gunner before any of the four Pratt-Whitney engines

were started. Power supplied by the "putt-putt" had to be switched on line to the main power source of the plane.

Otherwise the "juice" needed to start the B-29's four engines would have drained the generators.

In emergencies, the "putt-putt" could be used to close the bomb bay doors for example.

RCM:

Is a Radar-Counter-Measures Officer. Each group had 4-5 of these men who intercepted and sometimes

recorded Japanese radar signals and analyzed there characteristics. We could then exploit there vulnerabilities.

During WWII, this was very top secret, so little detail exists in any official records about what transpired.

The 73rd Bomb Wing on Saipan was composed of four very-heavy Bomb Groups, the 497th, the 498th, the 499th,

and the 500th. There were three squadrons in each group.

Additionally, the 313th Bomb Wing was assigned at North Field, Tinian, and the 58th Bomb Wing from the CBI was assigned to West Field, Tinian. The 314th and 315th Bomb Wings were both assigned to airfields on Guam.

RUNWAYS:

Eventually, Saipan had two parallel 8800 foot runways to launch their B-29s. A flagman would dispatch the planes from his assigned runway at appoximately one minute intervals, but staggered by 30 seconds from the other runway.

Thus, Runway A would dispatch a plane, and 30 seconds later Runway B would dispatch another plane, and this went on until all planes were airborne. If done properly, and there were no emergencies or aborted takeoffs, a plane would be lifting off from Saipan every 30 seconds.

PREFLIGHT:

Crew Inspection: Each member inspected to ensure he had his particular assigned equipment for his job, i.e. radar, navigator charts, etc. Plus his parachute, MaeWest, flak and survival gear.

Aircraft Inspection: A/C and Pilot checked all aspects of the plane, and each individual checked his particular area. Especially the gunners.

Props: The crew had to pull the props through at least four complete rotations to transfer oil from the

lower engine cylinders to the upper cylinders. This prevented cylinder damage due to oil seeping out of the top cylinder to the lower ones when the engines were not run.

ENGINE START UP:

Usually started from outboard left (#1) across to outboard (#4), but not manditory as we understand it.

A ground crew member always stood by each engine with a fire extinguisher when started, in case a fire broke

out in that engine. One ex-B29er told us if that occured, their rule of thumb was to shut everything down and

get away from that airplane.

PUTT-PUTT:

This little gasoline engine was usually started by the tail gunner before any of the four Pratt-Whitney engines

were started. Power supplied by the "putt-putt" had to be switched on line to the main power source of the plane.

Otherwise the "juice" needed to start the B-29's four engines would have drained the generators.

In emergencies, the "putt-putt" could be used to close the bomb bay doors for example.

RCM:

Is a Radar-Counter-Measures Officer. Each group had 4-5 of these men who intercepted and sometimes

recorded Japanese radar signals and analyzed there characteristics. We could then exploit there vulnerabilities.

During WWII, this was very top secret, so little detail exists in any official records about what transpired.

CREW ONBOARD POSITIONS DURING TAKE-OFFS AND LANDING.

Crewmen were always at their assigned stations during these phases of a mission.

Take-offs were the most dangerous during a mission due to the heavy weight a B-29 carried because of the fuel and bomb loads-of up to 140,000 pounds. Except the tail gunner who had to operate the Putt-Putt. Tail gunner Jean Allen explained he always had the Putt-Putt running to provide auxillary power during take-off and landing, but he

also had the emergency escape hatch opened in case he had to make a quick exit in case of a crash. When taking off from Saipan the B-29s would lift off and then dive 200 feet down the cliff toward the ocean to pick up extra speed, often so close

to the ocean that water sprayed everywhere. As one B-29er explained, the mission was most important so we stayed at our positions.

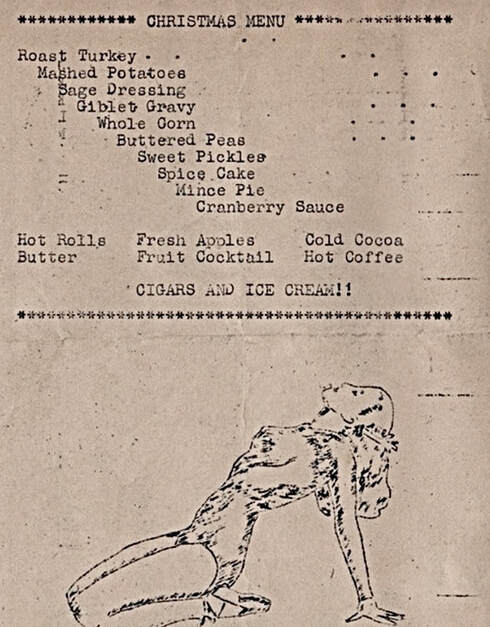

FOOD WARMERS:

Long flights averaging 14 hours in duration, meant the men were not only fatigued but also very hungry. Various crewmen have explained that some B-29s had food warmers, but others did not. Our Uncle Bob's crewmate and friend Doug Bulloch said his B-29 never had food warmers. His crew ate something he called " Austrailian bully-beef" sandwiches,

which was actully mutton. But, Ed Lawson stated his aircraft did have the food-warmers, and that the food was edible but not tasty. Ed said the food got very mushy but it was warm and they got very hungry. Many crews simply took sandwiches, snacks and candy bars with them and ate those. Usually after completion of their bomb runs and they were headed back to Saipan.

Crewmen were always at their assigned stations during these phases of a mission.

Take-offs were the most dangerous during a mission due to the heavy weight a B-29 carried because of the fuel and bomb loads-of up to 140,000 pounds. Except the tail gunner who had to operate the Putt-Putt. Tail gunner Jean Allen explained he always had the Putt-Putt running to provide auxillary power during take-off and landing, but he

also had the emergency escape hatch opened in case he had to make a quick exit in case of a crash. When taking off from Saipan the B-29s would lift off and then dive 200 feet down the cliff toward the ocean to pick up extra speed, often so close

to the ocean that water sprayed everywhere. As one B-29er explained, the mission was most important so we stayed at our positions.

FOOD WARMERS:

Long flights averaging 14 hours in duration, meant the men were not only fatigued but also very hungry. Various crewmen have explained that some B-29s had food warmers, but others did not. Our Uncle Bob's crewmate and friend Doug Bulloch said his B-29 never had food warmers. His crew ate something he called " Austrailian bully-beef" sandwiches,

which was actully mutton. But, Ed Lawson stated his aircraft did have the food-warmers, and that the food was edible but not tasty. Ed said the food got very mushy but it was warm and they got very hungry. Many crews simply took sandwiches, snacks and candy bars with them and ate those. Usually after completion of their bomb runs and they were headed back to Saipan.

The following image is original and subsequent zoom images are of portions of it...to refer back to based on comments below by J.Bowman.

Bomber of the 500th BG on their hardstands circa 21 Nov 1944 (881st Squadron)

These photographs are emotionally and historically important to our family and friends because they show both

of Uncle Bob's assigned aircraft, Z Square 6 and Z Square 8, parked together on their hardstands upon arrival on Saipan in November, 1944.

These are the only photographs where we have viewed the airplanes next to one another.

of Uncle Bob's assigned aircraft, Z Square 6 and Z Square 8, parked together on their hardstands upon arrival on Saipan in November, 1944.

These are the only photographs where we have viewed the airplanes next to one another.

...photograph that I recently received from David Reade, who found it in the National Archives. I'd actually seen this picture before, but not with such good resolution. The resolution is so good in fact that I was able to narrow down the time frame to between 21 and 29 November 1944 inclusive. How?

First, these are obviously B-29's of the 500th Bomb Group on Saipan. From the height and angle, I can tell that the picture was taken from a popular vantage point, the control tower alongside the south side of the Isley runway, with the camera pointed roughly ESE. The planes in the foreground are Z-28 and Z-29 of the 882nd Squadron. Behind them and receding into the left background are planes of the 881st Squadron -- from right to left, Z-5, Z-6, Z-7, Z-8, Z-9 and Z-10. behind Z-10 is I think a plane of the 499th Group, looks like V-2.

But the new revelation for me has to do with the three planes in the right background on the apron of Service Center B. Before, I couldn't make out their numbers, but now I can see that they are, from right to left, Z-45, Z-41 and Z-44 of the 883rd Squadron. Z-44 arrived on Saipan on 20 Nov 44 and Z-41 and Z-45 arrived the following day.

Furthermore, Z-44 was lost on a night mission to Tokyo on 29 Nov 44.

And no other plane in the 500th was ever numbered 44. In fact, this is the only picture of Z-44 that I know of.

Because these three planes arrived so close together and are not on their hardstands, I suspect that the date the picture was taken is closer to 21 than 29 Nov.

There's a lot to be seen in this picture if you look closely. Men and equipment can be seen around several of the planes. Another interesting feature is that Z-28 already has her name, "Old Ironsides", painted on.

That was quick, because she only arrived on Saipan on 20 Nov. Or maybe the name was painted on in the States or possibly in Hawaii, where Z-3, "Snafu-perfort", got hers. But I don't see names or artwork on any of the other planes in the picture. This fits, because I think December was when most of the artwork was applied.

On a personal note, Z-29, 42-65221, in the left foreground was the plane my father's crew flew from the States. But they would fly her on only one mission, 24 Nov, before switching to another plane.

One last thing, the high ground in the background is the northern part of Nafutan Point, which tapers off to the southeast.

( J.Bowman)

First, these are obviously B-29's of the 500th Bomb Group on Saipan. From the height and angle, I can tell that the picture was taken from a popular vantage point, the control tower alongside the south side of the Isley runway, with the camera pointed roughly ESE. The planes in the foreground are Z-28 and Z-29 of the 882nd Squadron. Behind them and receding into the left background are planes of the 881st Squadron -- from right to left, Z-5, Z-6, Z-7, Z-8, Z-9 and Z-10. behind Z-10 is I think a plane of the 499th Group, looks like V-2.

But the new revelation for me has to do with the three planes in the right background on the apron of Service Center B. Before, I couldn't make out their numbers, but now I can see that they are, from right to left, Z-45, Z-41 and Z-44 of the 883rd Squadron. Z-44 arrived on Saipan on 20 Nov 44 and Z-41 and Z-45 arrived the following day.

Furthermore, Z-44 was lost on a night mission to Tokyo on 29 Nov 44.

And no other plane in the 500th was ever numbered 44. In fact, this is the only picture of Z-44 that I know of.

Because these three planes arrived so close together and are not on their hardstands, I suspect that the date the picture was taken is closer to 21 than 29 Nov.

There's a lot to be seen in this picture if you look closely. Men and equipment can be seen around several of the planes. Another interesting feature is that Z-28 already has her name, "Old Ironsides", painted on.

That was quick, because she only arrived on Saipan on 20 Nov. Or maybe the name was painted on in the States or possibly in Hawaii, where Z-3, "Snafu-perfort", got hers. But I don't see names or artwork on any of the other planes in the picture. This fits, because I think December was when most of the artwork was applied.

On a personal note, Z-29, 42-65221, in the left foreground was the plane my father's crew flew from the States. But they would fly her on only one mission, 24 Nov, before switching to another plane.

One last thing, the high ground in the background is the northern part of Nafutan Point, which tapers off to the southeast.

( J.Bowman)

The video below by our friend Gary Boothe who has graciously agreed to allow us to embed it on our site is fantastic.

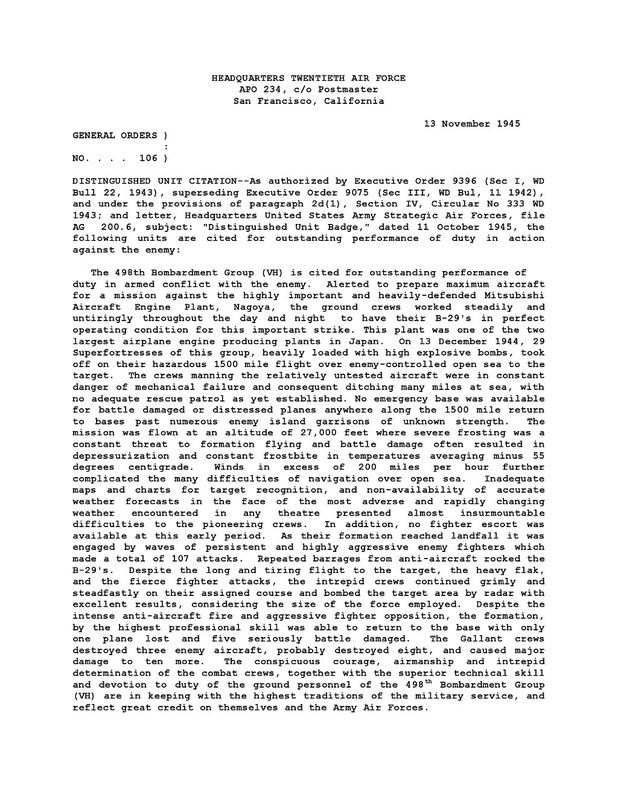

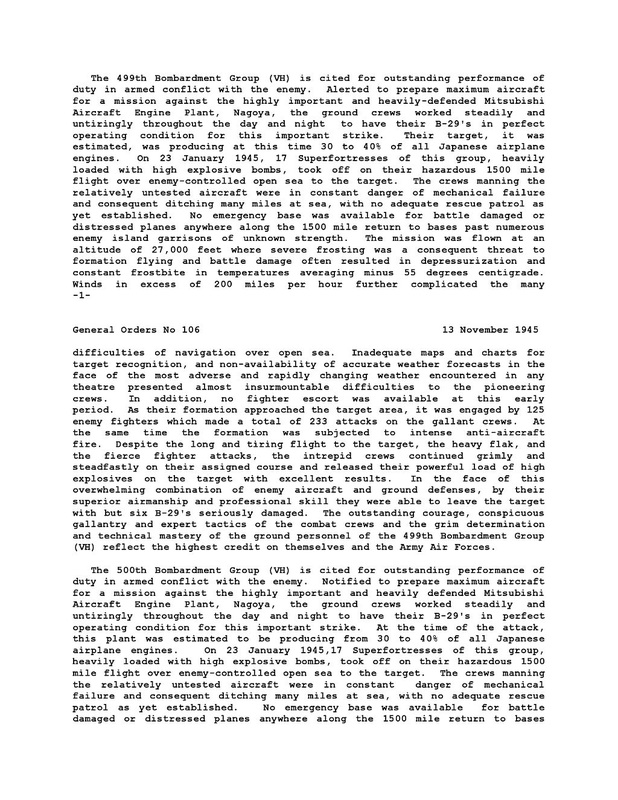

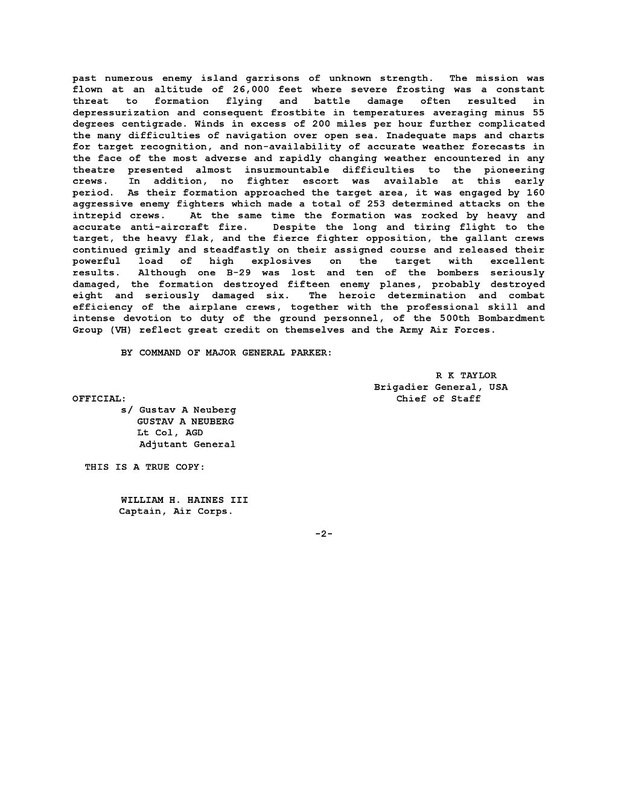

20th AF, General Order 106

for the 498th, 499th & 500th Bombardment Groups Unit Citation

(Research credit: Bill Streifer)

http://pc-mod-squad.com/B29/1945_13%20November_General%20Orders%20106.html

http://pc-mod-squad.com/B29/1945_13%20November_General%20Orders%20106.html

For an extremely comprehensive study of the B-29 bombing missions and personnel of the 500th Bomb Group, Saipan, 1944-45, view www.500thbombgroupb29.org website. Includes day to day detailed mission reports of all crews. A "must see" for everyone. Can also be accessed through our "links" tab

In the following photograph Sgt. Pilz is sitting on an indendiary bomb.

This bomb is an example of the ordnance our uncle's B-29, the Z Square 8, would have dropped on Kobe city the night they

were KIA.

This bomb is an example of the ordnance our uncle's B-29, the Z Square 8, would have dropped on Kobe city the night they

were KIA.

This plaque is located at the USAF National Museum in Dayton, Ohio

http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/photos/mediagallery.asp?galleryID=532&page=45

http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/photos/mediagallery.asp?galleryID=532&page=45

881st patch

Closing the shade on the rising sun of Japan

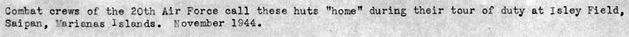

Isley Field 1945

Perspective is roughly south to north. In the foreground is the easternmost part of the 500th Bomb Group living area, with part of the 499th visible to the right. Just left of center you can make out the 500th's Surfside Theater, and to the right of it, at the deepest indentation of the coastline, is I believe the Officers Club.

Beyond the midground embankment are the working areas and some of the living areas of the 303rd and 330th Air Service Groups, which manned Service Center B. Along the embankment at right is Pendleton Bowl, the 330th theater.

Next up is the Service Center B apron, with four B-29's on it at left and a hangar at far right. Beyond that are hardstands, with 500th planes on the left and 499th planes on the right. Then come the Isley runways, with Magicienne Bay at right. And beyond the runways are hardstands of the 497th Group. (498th hardstands are out of the picture to the left.)

Beyond the midground embankment are the working areas and some of the living areas of the 303rd and 330th Air Service Groups, which manned Service Center B. Along the embankment at right is Pendleton Bowl, the 330th theater.

Next up is the Service Center B apron, with four B-29's on it at left and a hangar at far right. Beyond that are hardstands, with 500th planes on the left and 499th planes on the right. Then come the Isley runways, with Magicienne Bay at right. And beyond the runways are hardstands of the 497th Group. (498th hardstands are out of the picture to the left.)

TAIL OR SIDE, AIRPLANE NUMBERS:

The 881st Squadron was assigned numbers 1-19. The 882nd Squadron numbers 21-39, and the

883rd Squadron numbers 41-59. (20, 40, and numbers 60 and above were not used.)

Originally, the 500th was assigned 30 airplanes, 10 per squadron, numbered 1-10, 21-30,

and 41-50. (Uncle Bob was in this initial group.) As more replacement airplanes arrived, numbers

were added to each squadron, such as Z Square 11, Z Square 12, or Z Square 13 in the 881st Squadron.

By wars end, each squadron had 16-17 airplanes. When a plane was lost or transferred, it's replacement usually received the same number, as in the case of the Z Square 6, or Z Square 8.

A few B-29s also carried more than one number during their careers. One airplane, 42-24743,

served in all 3 squadrons, first as Z Square 8, then Z Square 56, and finally as Z Square 25. These number changes, or squadron transfers, usually occured when and airplane was grounded for extensive repairs or maintenance, and a replacement aircraft was assigned it's number.

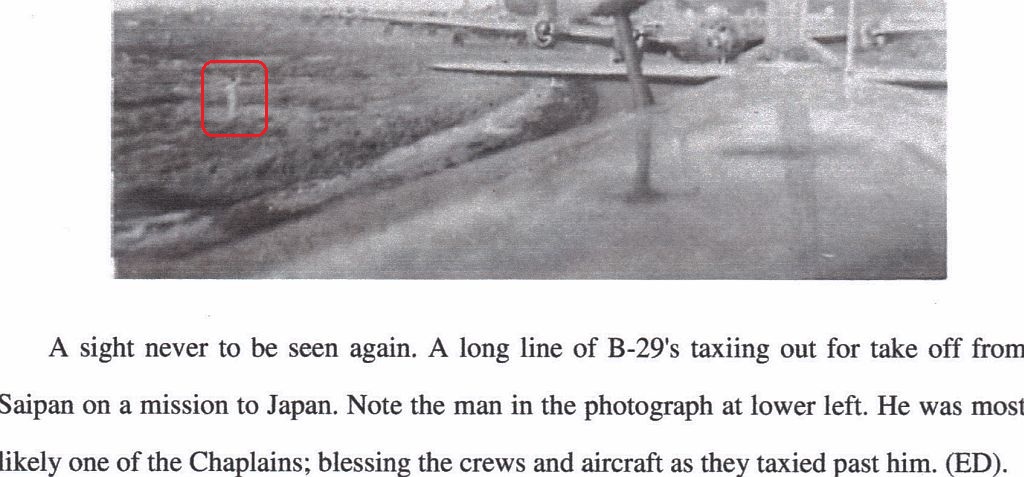

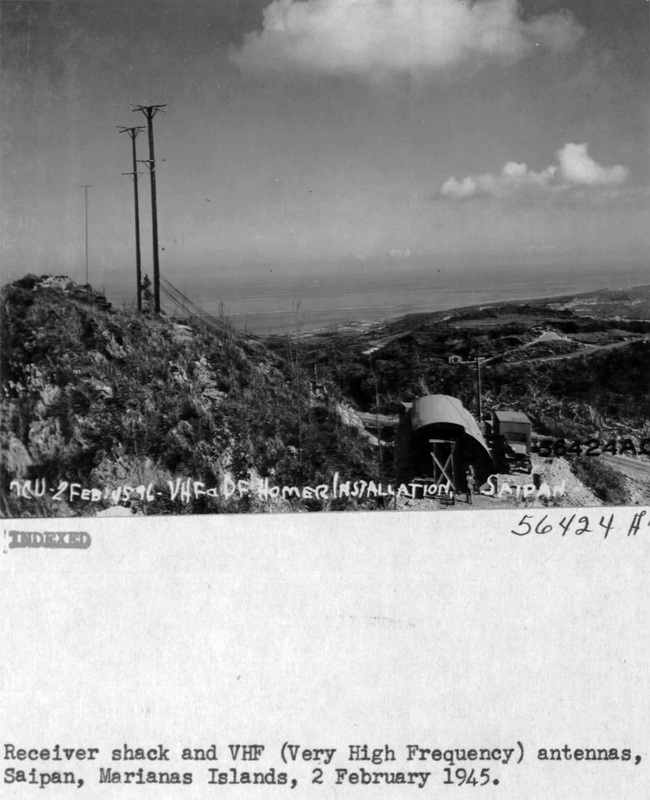

VOICE CALL SIGNS:

Voice call signs or voice communication (VHF) were usually only good for 50-60 mile distances.

These signals don't bend particularly with the curvature of the earth and are direct-line systems. These signs used the unit's call word plus a number. Happy 5 would be A Square 5, and Dagwood 28 would be Z Square 28 for example.

MORSE CALL SIGNS:

Morse or HF would range for several hundred miles and were better adapted to conform to the curvature of the earth.

They were a combination of numbers of letters. Early on, the call sign for the Z Square 6 was 6V534, where the 6 was the airplane's tail number and the 534 ws the 500th Bomb Group. (See Charles Maples) #531 was the 497th Bomb Group, #532 was the 498th Bomb Group, and #533 was the 499th Bomb Group.

So, T Square 29 of the 498th Bomb Group was 29V532, or V Square 44 of the 499th Bomb Group would be 44V533.

For example, the call sign for H.Q. Saipan was 00V530. When the crew of Captain Joseph Irvin was lost on

27 November 1944, their call sign was 2V534. The last contact anyone had with them was radio operator Charles Maples, 6V534, of the Z Square 6, "Draggin Lady." Irvin had been on the wing of Major Robert Goldsworthy's aircraft, but because of battle damage the Irvin plane faded from view and was never seen again. No survivors were ever found, even though SSgt Maples relayed their final position to Saipan.

The 881st Squadron was assigned numbers 1-19. The 882nd Squadron numbers 21-39, and the

883rd Squadron numbers 41-59. (20, 40, and numbers 60 and above were not used.)

Originally, the 500th was assigned 30 airplanes, 10 per squadron, numbered 1-10, 21-30,

and 41-50. (Uncle Bob was in this initial group.) As more replacement airplanes arrived, numbers

were added to each squadron, such as Z Square 11, Z Square 12, or Z Square 13 in the 881st Squadron.

By wars end, each squadron had 16-17 airplanes. When a plane was lost or transferred, it's replacement usually received the same number, as in the case of the Z Square 6, or Z Square 8.

A few B-29s also carried more than one number during their careers. One airplane, 42-24743,

served in all 3 squadrons, first as Z Square 8, then Z Square 56, and finally as Z Square 25. These number changes, or squadron transfers, usually occured when and airplane was grounded for extensive repairs or maintenance, and a replacement aircraft was assigned it's number.

VOICE CALL SIGNS:

Voice call signs or voice communication (VHF) were usually only good for 50-60 mile distances.

These signals don't bend particularly with the curvature of the earth and are direct-line systems. These signs used the unit's call word plus a number. Happy 5 would be A Square 5, and Dagwood 28 would be Z Square 28 for example.

MORSE CALL SIGNS:

Morse or HF would range for several hundred miles and were better adapted to conform to the curvature of the earth.

They were a combination of numbers of letters. Early on, the call sign for the Z Square 6 was 6V534, where the 6 was the airplane's tail number and the 534 ws the 500th Bomb Group. (See Charles Maples) #531 was the 497th Bomb Group, #532 was the 498th Bomb Group, and #533 was the 499th Bomb Group.

So, T Square 29 of the 498th Bomb Group was 29V532, or V Square 44 of the 499th Bomb Group would be 44V533.

For example, the call sign for H.Q. Saipan was 00V530. When the crew of Captain Joseph Irvin was lost on

27 November 1944, their call sign was 2V534. The last contact anyone had with them was radio operator Charles Maples, 6V534, of the Z Square 6, "Draggin Lady." Irvin had been on the wing of Major Robert Goldsworthy's aircraft, but because of battle damage the Irvin plane faded from view and was never seen again. No survivors were ever found, even though SSgt Maples relayed their final position to Saipan.

Bombing newspaper articles

Silver wings in the moonlight

Smiling swiftly through the night.

With a rondevouz with destiny

Before the morning light.

There's a place called Fuji Ami

Where the bombing runs begin.

It's a straight line to the target

Will we stand on earth again?

Ther's a place we call Flak Alley

The the combat crews all dread,

Where the shells burst all around us

Someone down there wants us dead.

Fiery fingers reach to grab us

As the searchlights scan the sky.

Then we are caught in their clutches.

We can't escape them, though we try.

Shrapnel then expldes around us

As the shells light up the night.

We can feel the aircraft shudder,

Then continue in its flight.

We continue onward, forward.

'Til we hear the bombardier say,

The words that we are waiting for,

As he announces, "Bombs away!"

Then the Zeroes are coming at us

At last, now we can use our guns.

They harnass us to the coastline

As we fly toward the Rising Sun.

Yes, our plane is badly wounded

But we still hear the engines drone.

Still we pray that we will make it,

It's 15 hundred miles to home.

We can hear our engines labor

As we struggle through the night.

We still pray that we can make it

We have not yet won this fight.

Silver wings now in the daylight

And we have our base in sight.

Soon we will come in for a landing.

We'll not forget this bitter night.

What a blessing! What a feeling!

As we start to earth again.

Still it is a short lived pleasure,

Tomorrow we must go out again.

We don't fight for fame or glory.

We have done this job for pay.

I have flown for 18 hours

And I earned five bucks today.

Dedicated to the Bomber Crew 60, 499th Bomb Group, 879th Bomb Squad, Saipan Island 1944-1945. W.D. Royster

With gratitude and fondness for Mr. William "Bill" Royster, who took his final flight on 17 February 2011. Thanks for everything, Bill.

*We loved this poem and thought that it applies to all the Bomb Groups operating out of Isley Field on Siapan

Smiling swiftly through the night.

With a rondevouz with destiny

Before the morning light.

There's a place called Fuji Ami

Where the bombing runs begin.

It's a straight line to the target

Will we stand on earth again?

Ther's a place we call Flak Alley

The the combat crews all dread,

Where the shells burst all around us

Someone down there wants us dead.

Fiery fingers reach to grab us

As the searchlights scan the sky.

Then we are caught in their clutches.

We can't escape them, though we try.

Shrapnel then expldes around us

As the shells light up the night.

We can feel the aircraft shudder,

Then continue in its flight.

We continue onward, forward.

'Til we hear the bombardier say,

The words that we are waiting for,

As he announces, "Bombs away!"

Then the Zeroes are coming at us

At last, now we can use our guns.

They harnass us to the coastline

As we fly toward the Rising Sun.

Yes, our plane is badly wounded

But we still hear the engines drone.

Still we pray that we will make it,

It's 15 hundred miles to home.

We can hear our engines labor

As we struggle through the night.

We still pray that we can make it

We have not yet won this fight.

Silver wings now in the daylight

And we have our base in sight.

Soon we will come in for a landing.

We'll not forget this bitter night.

What a blessing! What a feeling!

As we start to earth again.

Still it is a short lived pleasure,

Tomorrow we must go out again.

We don't fight for fame or glory.

We have done this job for pay.

I have flown for 18 hours

And I earned five bucks today.

Dedicated to the Bomber Crew 60, 499th Bomb Group, 879th Bomb Squad, Saipan Island 1944-1945. W.D. Royster

With gratitude and fondness for Mr. William "Bill" Royster, who took his final flight on 17 February 2011. Thanks for everything, Bill.

*We loved this poem and thought that it applies to all the Bomb Groups operating out of Isley Field on Siapan

High Flight

A well known military aviation poem is "High Flight", written by John G. Magee on September 3, 1941. The version that most nearly follows the original manuscript is as follows:

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,-and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of-wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there,

I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air....

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I've topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew-

And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God

Magee was born in Shanghai, China, of missionary parents-an American father and an English mother, and spoke Chinese before English. He was educated at Rugby school in England and at Avon Old Farms School in Connecticut. He won a Scholarship to Yale, but instead joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in late 1940, trained in Canada, and was sent to Britain. He flew in a Spitfire squadron and was killed on a routine training mission on December 11, 1941.

The sonnet above was sent to his parents written on the back of a letter which said, "I am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet, and was finished soon after I landed." He also wrote of his course ending soon and of his then going on operations, and added, "I think we are very lucky as we shall just be in time for the autumn blitzes(which are certain to come)."

Magee's parents lived in Washington, D.C., at the time of his death, and the sonnet came to the attention of the Librarian of Congress, Archibald MacLeish. He acclaimed Magee the first poet of the War, and included the poem in an exhibition of poems of "faith and freedom" at the Library of Congress in February 1942. The poem was then widely reprinted, and the RCAF distributed plaques with the words to all airfields and training stations.

The reprintings vary in punctuation, capitalization, and indentation from the original manuscript, which is in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Some portions are faded and difficult to read, but the version above follows Magee's as exactly as can be made out, following his pencilled note on another poem, "if anyone should want this please see that it is accurately copied, capitalized, and punctuated." Nearly all versions use "...even eagle," but careful scrutiny show that it was "ever", formed exactly like the preceding "never".

President Ronald Reagan quoted from the first and last lines in a televised address to the nation after the space shuttle Challenger exploded, January 28, 1986.

A well known military aviation poem is "High Flight", written by John G. Magee on September 3, 1941. The version that most nearly follows the original manuscript is as follows:

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds,-and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of-wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there,

I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air....

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I've topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew-

And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God

Magee was born in Shanghai, China, of missionary parents-an American father and an English mother, and spoke Chinese before English. He was educated at Rugby school in England and at Avon Old Farms School in Connecticut. He won a Scholarship to Yale, but instead joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in late 1940, trained in Canada, and was sent to Britain. He flew in a Spitfire squadron and was killed on a routine training mission on December 11, 1941.

The sonnet above was sent to his parents written on the back of a letter which said, "I am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet, and was finished soon after I landed." He also wrote of his course ending soon and of his then going on operations, and added, "I think we are very lucky as we shall just be in time for the autumn blitzes(which are certain to come)."

Magee's parents lived in Washington, D.C., at the time of his death, and the sonnet came to the attention of the Librarian of Congress, Archibald MacLeish. He acclaimed Magee the first poet of the War, and included the poem in an exhibition of poems of "faith and freedom" at the Library of Congress in February 1942. The poem was then widely reprinted, and the RCAF distributed plaques with the words to all airfields and training stations.

The reprintings vary in punctuation, capitalization, and indentation from the original manuscript, which is in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Some portions are faded and difficult to read, but the version above follows Magee's as exactly as can be made out, following his pencilled note on another poem, "if anyone should want this please see that it is accurately copied, capitalized, and punctuated." Nearly all versions use "...even eagle," but careful scrutiny show that it was "ever", formed exactly like the preceding "never".

President Ronald Reagan quoted from the first and last lines in a televised address to the nation after the space shuttle Challenger exploded, January 28, 1986.

B-29s dropping bombs on target

"This dramatic photograph of a rare daylight incendiary mission was taken on 29 May 1945 over Yokohama by Sgt Howard Clos, left gunner on the Curtis crew, flying Z-12.. The planes are from the 881st Bomb Squadron. The B-29 in the foreground is Z-19, 42-63435, "Sna Pe Fort", flown as usual by the Althoff crew. Identifiable in the background from right to left are Z-14, 42-65346, unnamed, usually flown by the Mather crew; Z-15, 44-69944, "Fire Bug", usually flown by the Pearson crew; and Z-11, 42-24744, "Lucky Eleven", Lewis crew. The plane on the far left is not identifiable."

(J.Bowman)

(J.Bowman)

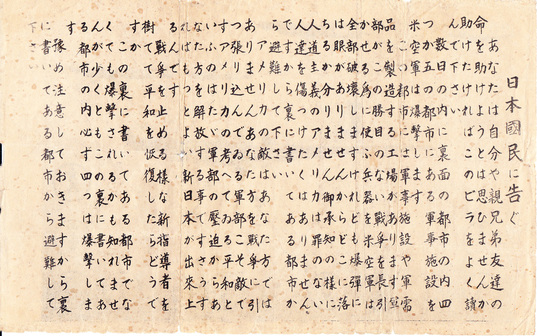

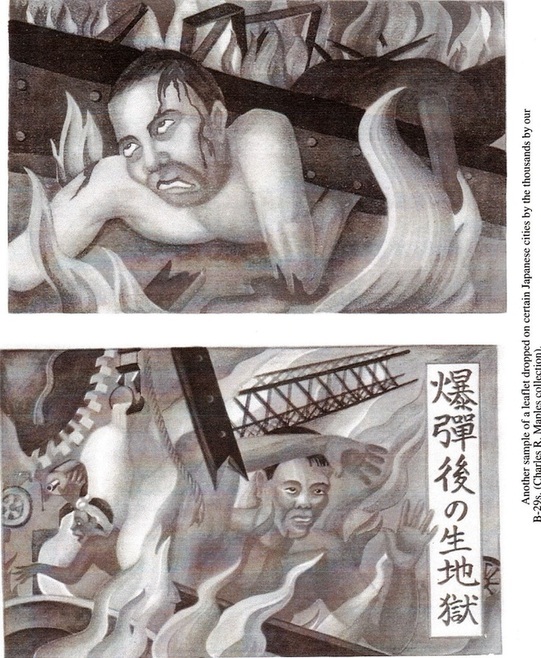

Actual Pre-Bombing Leaflets dropped by the 73rd Wing

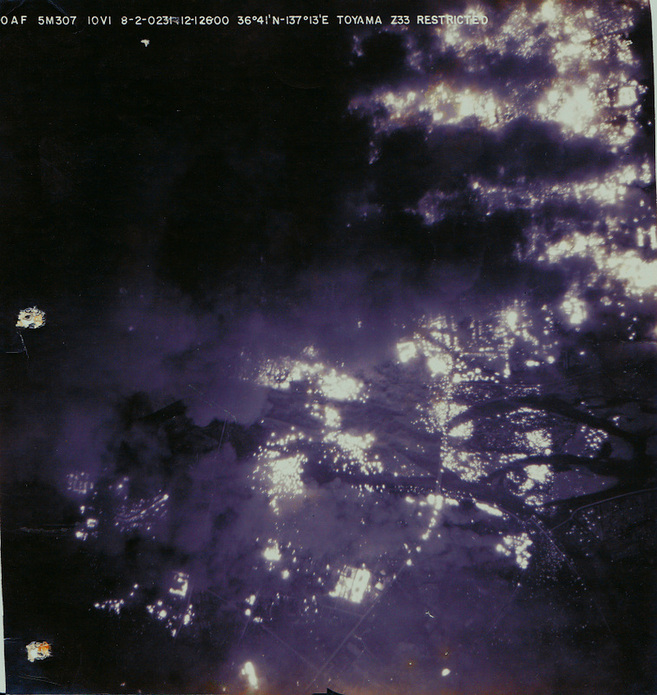

Radar Camera Images

Below are images taken from the radar camera of S/Sgt. Jack L. Heffner (radar) of "Holy Joe". They are the types of images our Uncle Bob would have seen through his radar as well. The second image is just one image of the effectiveness of an incendiary raid.

(if you look closely just above the roadway intersection, you can see the actual bomb hits)

(if you look closely just above the roadway intersection, you can see the actual bomb hits)

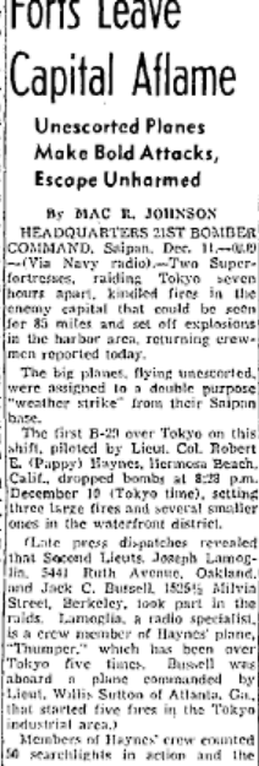

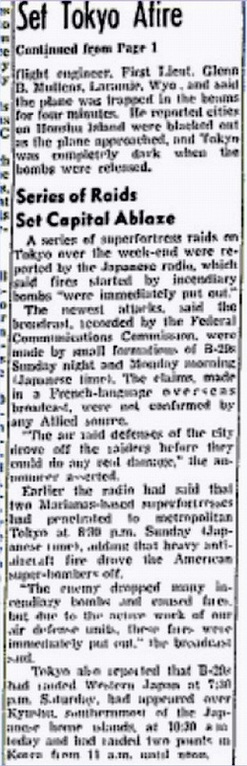

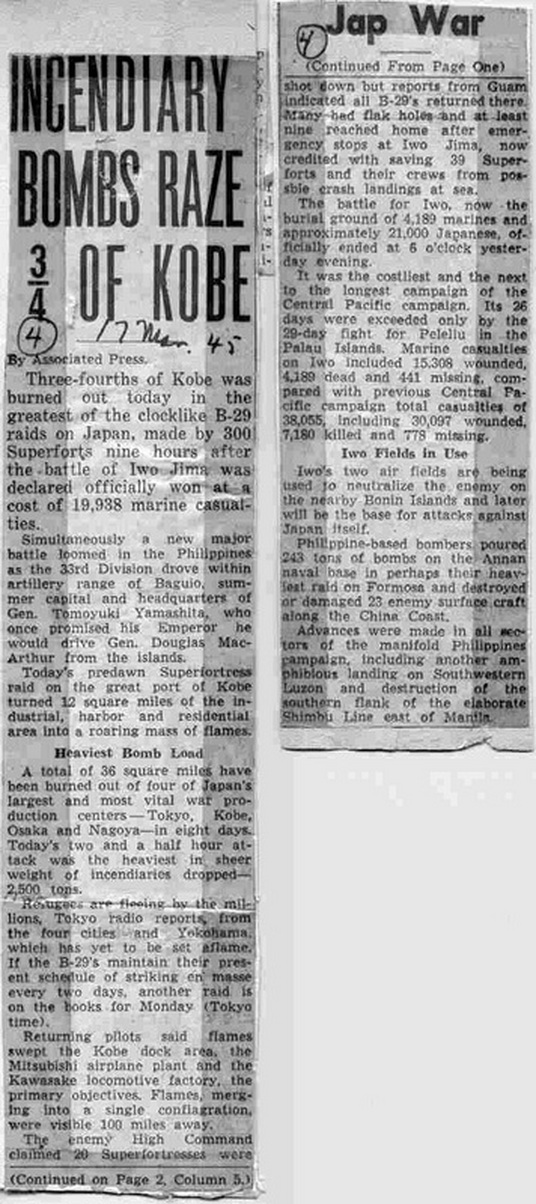

Incendiary Raids New clipping by Aassociated Press

On 20 January 1945, General Curtis LeMay replaced General Haywood Hansel as commander of the 21st Bomber Command in the Mariana Islands. Hansel's refusal to alter his schedule of high-altitude bombing of Japan was no doubt the cause for his removal. High-altitude bombing of Japan's industrial areas had proven extemely ineffective, in large part due to the velocity of the winds that we now recognize as the "jet stream."

LeMay's radical new changes in bombing techiques would not only devastate the Japanese cities, but they also "shocked" his own flight crews.

Effective the first week of March, 1945, the bomber crews would bomb Japanese cities at altitudes of 5000 to 8000 feet, at "night", and would do so flying individually all the way to the target and back. Initially, all gunners would be left behind except the tail gunner, who would act as a "spotter." All guns and ammunition would also be removed from the B-29s to save weight so the bomb load could be increased.

Washington actually made the decision to use fire-bombs (incendiary) on the Japanese cities, but it was LeMay's choice to do it at such low altitudes. LeMay did not view bombing Japanese cities as unethical or immoral because many war products were made in Japanese homes, and Japanese men, women, and children worked in the factories. LeMay felt that this work force had to be destroyed.

LeMay's radical new changes in bombing techiques would not only devastate the Japanese cities, but they also "shocked" his own flight crews.

Effective the first week of March, 1945, the bomber crews would bomb Japanese cities at altitudes of 5000 to 8000 feet, at "night", and would do so flying individually all the way to the target and back. Initially, all gunners would be left behind except the tail gunner, who would act as a "spotter." All guns and ammunition would also be removed from the B-29s to save weight so the bomb load could be increased.

Washington actually made the decision to use fire-bombs (incendiary) on the Japanese cities, but it was LeMay's choice to do it at such low altitudes. LeMay did not view bombing Japanese cities as unethical or immoral because many war products were made in Japanese homes, and Japanese men, women, and children worked in the factories. LeMay felt that this work force had to be destroyed.

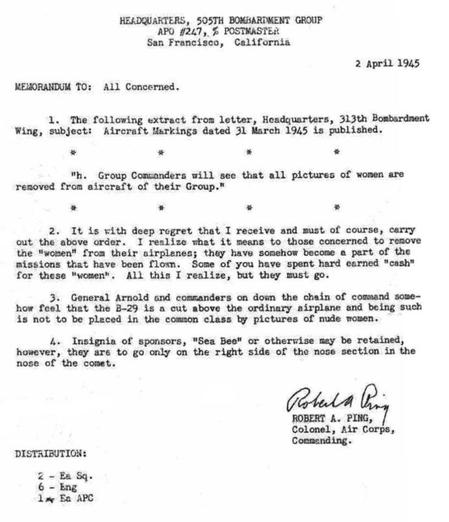

There has been a lot of speculation about General Lemay's order to leave all gunners behind, and remove all guns and ammunition from the B-29s on the low-level, incendiary raids to Japan commencing on 9 March 1945. And whether these orders were strictly followed.

The gunners were more than just gunners, they were the "spotters or scanners" for the pilots. They monitored problems with

the engines, ensured the flaps were in the correct position, and confirmed the bomb bay doors and wing wheel doors were operating properly. They also observed the action outside the aircraft, including the movement of other B-29s that might be around them.

According to some crew members, they found a way around LeMay's order, or circumvented it. Bill Royster was a tail gunner in the 499th Bomb Group, and he told Jim Bowman that his crew decided that what LeMay said was just a suggestion. A/C James Farrell of the 500th Bomb Group states that he never flew a mission without guns.

LeMay was extremely astute and intuitive and probably realized the positive effect it had on the crews to have some guns armed and at the ready on these missions. No one was ever disciplined for having guns or ammunitions during this time.

In fact, the night our Uncle Bob and his crew were rammed over Kobe on 17 March 1945, they carried a full crew of eleven, and the tail gunner, Ruben A. Wray, definitely had armed guns in his position.

The gunners were more than just gunners, they were the "spotters or scanners" for the pilots. They monitored problems with

the engines, ensured the flaps were in the correct position, and confirmed the bomb bay doors and wing wheel doors were operating properly. They also observed the action outside the aircraft, including the movement of other B-29s that might be around them.

According to some crew members, they found a way around LeMay's order, or circumvented it. Bill Royster was a tail gunner in the 499th Bomb Group, and he told Jim Bowman that his crew decided that what LeMay said was just a suggestion. A/C James Farrell of the 500th Bomb Group states that he never flew a mission without guns.

LeMay was extremely astute and intuitive and probably realized the positive effect it had on the crews to have some guns armed and at the ready on these missions. No one was ever disciplined for having guns or ammunitions during this time.

In fact, the night our Uncle Bob and his crew were rammed over Kobe on 17 March 1945, they carried a full crew of eleven, and the tail gunner, Ruben A. Wray, definitely had armed guns in his position.

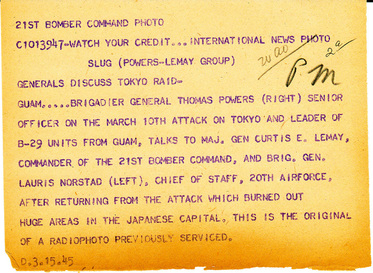

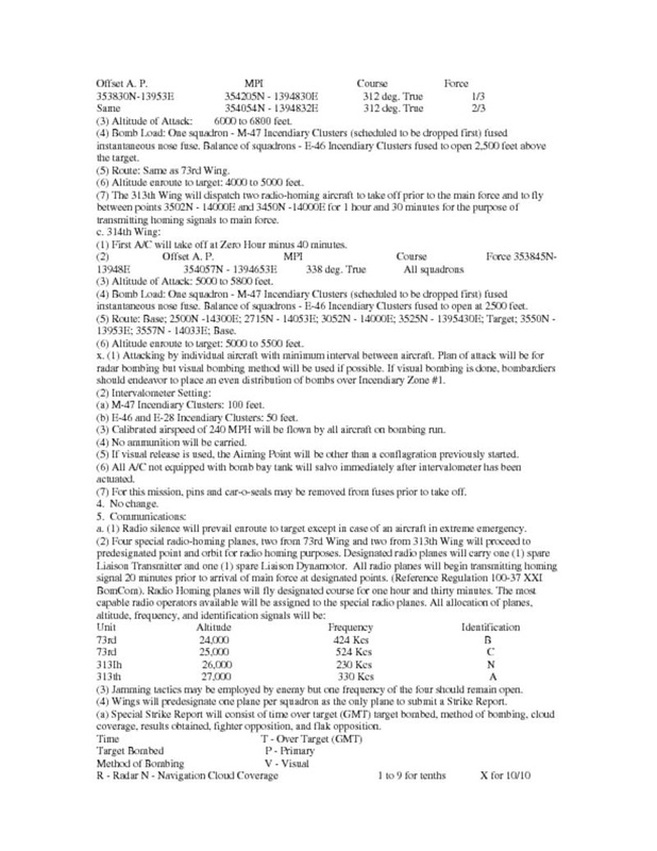

Tokyo Field Order for 09 March 1945

(Courtesy Marvin Demanzuk)

| tokyofieldorder9mar45.pdf | |

| File Size: | 137 kb |

| File Type: | |

The field order document as images:

RCM: Radar Counter Measures information

Your uncle would no doubt also have been very interested in these activities. He probably worked side by side with RCM officers who occasionally shared his small compartment and operated the recording and jamming equipment, but Bob's primary job was of course to use his radar to help with navigation and bombing.

This newsletter shows that in addition to knowing how to operate their equipment the RCM officers had to have a thorough knowledge of both US and Japanese equipment and tactics. I would guess that the majority of people

had no idea how complicated their job was.

(J.Bowman)

This newsletter shows that in addition to knowing how to operate their equipment the RCM officers had to have a thorough knowledge of both US and Japanese equipment and tactics. I would guess that the majority of people

had no idea how complicated their job was.

(J.Bowman)

| april_1945_rcm_newsletter.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1728 kb |

| File Type: | |

(the pdf above is interesting reading from D.Comella regarding his Uncle Joseph LaMoglia and RCM officers role)

This newsletter illustrates very well the breadth of knowledge the RCM officers had to possess. They had to understand the capabilities of their own equipment, the enemy's equipment, the technical aspects of bombing and navigation, both friendly and enemy tactics, and more. Quite a load.

Some parts of the newsletter are very technical. To help explain, "rope" was long strips of aluminum foil, cut to lengths corresponding to the operating frequencies of the enemy radar. This is called defensive or passive jamming.

The RCM officers also used jamming transmitters to send out signals to interfere with enemy radar frequencies. This is called offensive or active jamming. Spot jamming means focusing your jamming signal on a single frequency point. Barrage jamming means jamming a band of frequencies. Regarding this, bear in mind that the more you disperse

your signal, the weaker and less effective it will be at any one point.

The RCM officers had a limited capability to record enemy radar signals on acetate disks for later analysis and study -- frequency length, strength, pulse, etc.

Ferrets were planes specially configured for RCM work, i.e., probably filled with comms equipment, receivers, jammers, recorders, rope and more. Prior to the use of ferrets, the RCM officers had to have their specialized equipment

installed in regular B-29's before each mission and then removed afterwards.

I was especially intrigued by the modifications made to the radar room to accommodate the RCM officers (pages 4-5). Note the installation of an extra seat in the radar compartment. I believe that prior to this the RCM officers had to sit on the toilet to operate their equipment. The addition of interphone and oxygen plug-ins would have ben very useful, because without the interphone the RCM would be out of the loop, and without an oxygen plug-in he would somehow have to use a portable oxygen bottle while operating his equipment when unpressurized and above 10,000 feet or so.

(J. Bowman)

This newsletter illustrates very well the breadth of knowledge the RCM officers had to possess. They had to understand the capabilities of their own equipment, the enemy's equipment, the technical aspects of bombing and navigation, both friendly and enemy tactics, and more. Quite a load.

Some parts of the newsletter are very technical. To help explain, "rope" was long strips of aluminum foil, cut to lengths corresponding to the operating frequencies of the enemy radar. This is called defensive or passive jamming.

The RCM officers also used jamming transmitters to send out signals to interfere with enemy radar frequencies. This is called offensive or active jamming. Spot jamming means focusing your jamming signal on a single frequency point. Barrage jamming means jamming a band of frequencies. Regarding this, bear in mind that the more you disperse

your signal, the weaker and less effective it will be at any one point.

The RCM officers had a limited capability to record enemy radar signals on acetate disks for later analysis and study -- frequency length, strength, pulse, etc.

Ferrets were planes specially configured for RCM work, i.e., probably filled with comms equipment, receivers, jammers, recorders, rope and more. Prior to the use of ferrets, the RCM officers had to have their specialized equipment

installed in regular B-29's before each mission and then removed afterwards.

I was especially intrigued by the modifications made to the radar room to accommodate the RCM officers (pages 4-5). Note the installation of an extra seat in the radar compartment. I believe that prior to this the RCM officers had to sit on the toilet to operate their equipment. The addition of interphone and oxygen plug-ins would have ben very useful, because without the interphone the RCM would be out of the loop, and without an oxygen plug-in he would somehow have to use a portable oxygen bottle while operating his equipment when unpressurized and above 10,000 feet or so.

(J. Bowman)

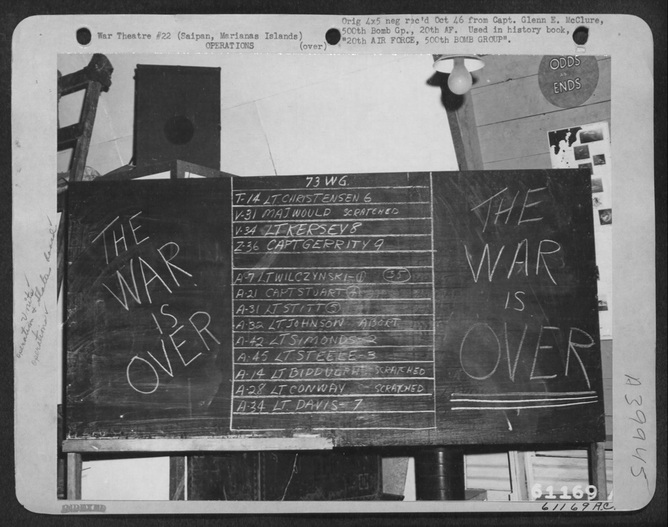

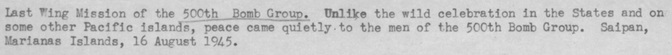

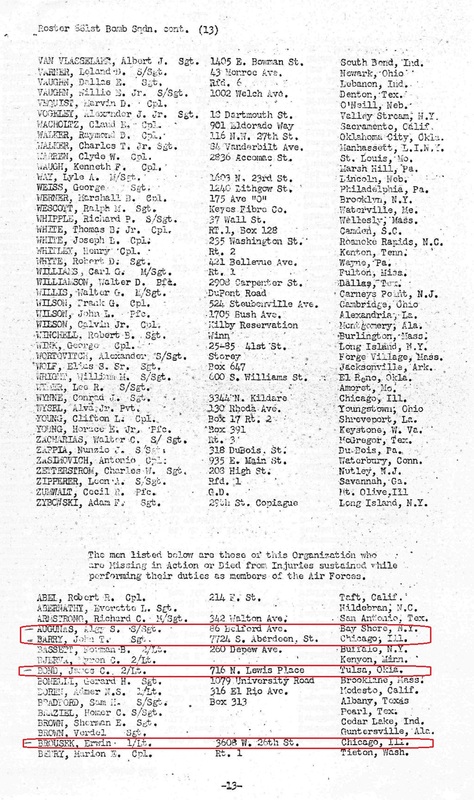

The official USAAF notice of those MIA, including Uncle Bob and Fitz crew of Z-8