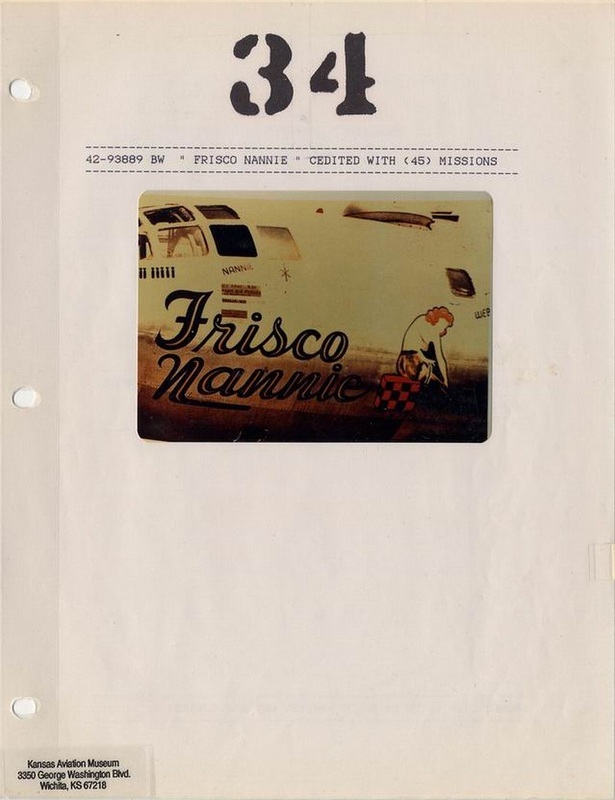

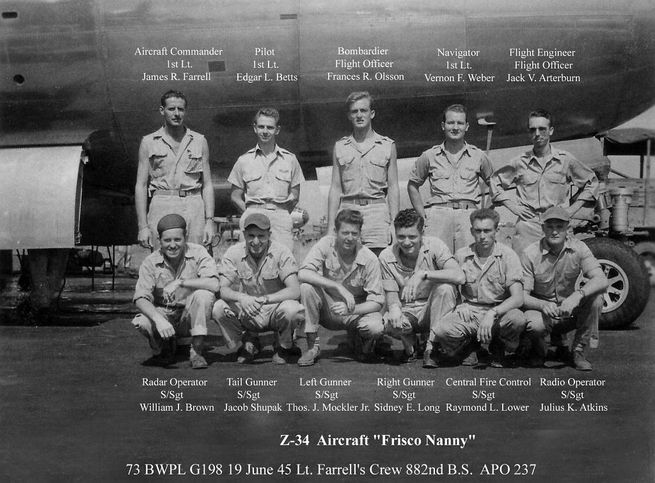

Colonel James R. Farrell of Z-34 "Frisco Nannie"

"Most crews thought it would be a disaster.....but, ours not to reason why - Ours but to do or, etc...."

- James Farrell on the low level incendiary bombing missions on Japanese cities beginning 9 March 1945

- James Farrell on the low level incendiary bombing missions on Japanese cities beginning 9 March 1945

24 July 45-Target: OSAKA arsenal.

This would be the final mission for A/C James Farrell. Lt. Farrell had a reputation for getting through to the target,

no matter what.

From his first mission on 24 Dec 1944 until his last mission to Osaka, he had had only two aborts, and had bombed the primary target on 34 of his 35 missions. An incredible percentage. He also had flown a practice mission to Iwo Jima. After completing his mission, he remained on Saipan and assisted in pilot instructions, test flights etc. where he would finally be promoted to Captain.

This would be the final mission for A/C James Farrell. Lt. Farrell had a reputation for getting through to the target,

no matter what.

From his first mission on 24 Dec 1944 until his last mission to Osaka, he had had only two aborts, and had bombed the primary target on 34 of his 35 missions. An incredible percentage. He also had flown a practice mission to Iwo Jima. After completing his mission, he remained on Saipan and assisted in pilot instructions, test flights etc. where he would finally be promoted to Captain.

Col. James R. Farrell took his last flight on 29 October 2013. He will be missed by all of us who knew him.

November 11, 2013

Veteran’s Day Tribute to My Dad

by M. Cohan

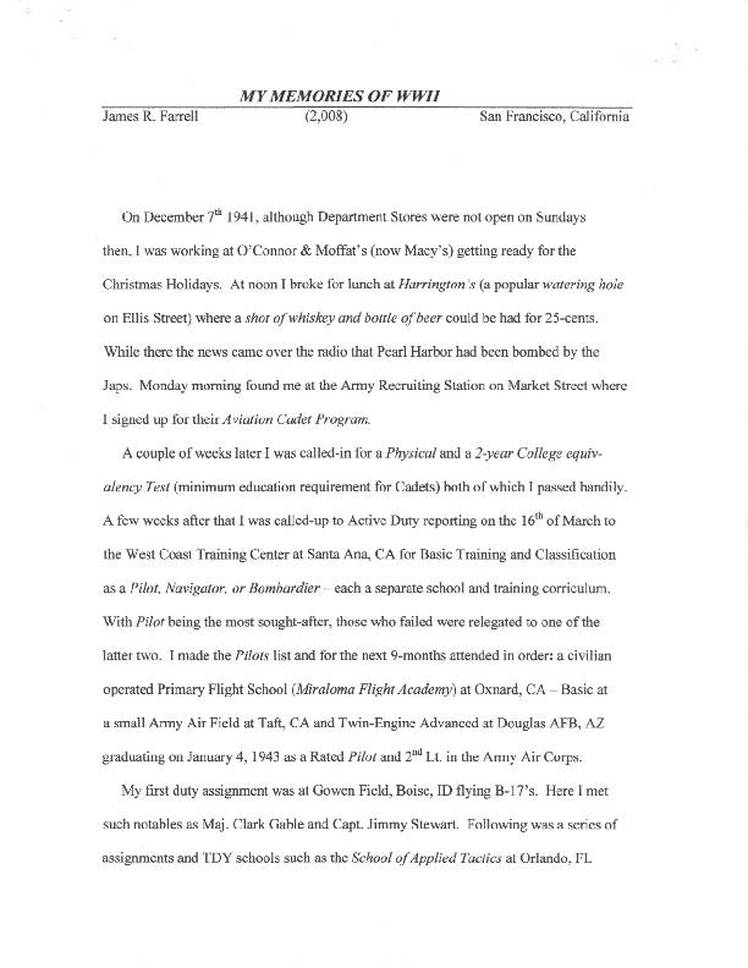

My Dad passed away last month at the age of 91. As a child of the Depression, he was working by the time he was 8 years old and hopping freight trains up and down the West Coast by the age of 10. He dropped out of high school as a sophomore to get work. When he enlisted in the Army Air Corp, his boss fired him so he wouldn’t have to re-hire him when he returned from the war. The men and women who served in World War II returned as heroes, but seldom spoke of their experiences. Until I started attending the reunions of the 73rd Bomb Wing Association with my Dad, I knew very little of his involvement in that war. Ed Lawson of the 500 Bomb Group sent me this upon learning of my Dad’s passing: “He was the aircraft commander of Z Square 34, Frisco Nannie and completed 35 missions. While many air crew personnel received an award of the Distinguished Flying Cross, he received a second DFC with the following citation: First Lieutenant James R Farrell, 0735068, 882nd, Bombardment Squadron, 500th Bombardment Group, Air Corps United States Army. For extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight on 25 May 1945. Lieutenant Farrell was Airplane Commander of a B-29 aircraft which flew from a base in the Marianas Islands on a night bombing mission against the heavily defended city of Tokyo, Japan. En route to the target rapidly changing and adverse weather conditions made navigation extremely difficult and serious mechanical difficulties necessitated excessive fuel consumption. Despite these obstacles, numerous search-lights and intense anti-aircraft fire, Lieutenant Farrell made an excellent radar bomb run and all bombs fell on the target. Immediately after bombs away heavy flak and violent turbulence were encountered and he underwent continuing fighter attacks from the target area to a point one hundred miles out to sea. Attacks by Japanese flying bombs created additional hazards requiring Lieutenant Farrell to employ evasive tactics. His courage and determination in the face of enemy opposition combined with his skill and professional ability which made possible the successful accomplishment of this mission reflect great credit on himself and the Army Air Forces. Jim had a distinguished career in civilian life and was a popular member of the 73rd Bomb Group Association and the 500th Bomb Group Memorial Association.” Although not shy, my Dad was a private person and very humble. He was adamant about not having a funeral or memorial service. This is my little tribute to the man who inspired me with his strong work ethic, his positive attitude and unceasing optimism.

Veteran’s Day Tribute to My Dad

by M. Cohan

My Dad passed away last month at the age of 91. As a child of the Depression, he was working by the time he was 8 years old and hopping freight trains up and down the West Coast by the age of 10. He dropped out of high school as a sophomore to get work. When he enlisted in the Army Air Corp, his boss fired him so he wouldn’t have to re-hire him when he returned from the war. The men and women who served in World War II returned as heroes, but seldom spoke of their experiences. Until I started attending the reunions of the 73rd Bomb Wing Association with my Dad, I knew very little of his involvement in that war. Ed Lawson of the 500 Bomb Group sent me this upon learning of my Dad’s passing: “He was the aircraft commander of Z Square 34, Frisco Nannie and completed 35 missions. While many air crew personnel received an award of the Distinguished Flying Cross, he received a second DFC with the following citation: First Lieutenant James R Farrell, 0735068, 882nd, Bombardment Squadron, 500th Bombardment Group, Air Corps United States Army. For extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight on 25 May 1945. Lieutenant Farrell was Airplane Commander of a B-29 aircraft which flew from a base in the Marianas Islands on a night bombing mission against the heavily defended city of Tokyo, Japan. En route to the target rapidly changing and adverse weather conditions made navigation extremely difficult and serious mechanical difficulties necessitated excessive fuel consumption. Despite these obstacles, numerous search-lights and intense anti-aircraft fire, Lieutenant Farrell made an excellent radar bomb run and all bombs fell on the target. Immediately after bombs away heavy flak and violent turbulence were encountered and he underwent continuing fighter attacks from the target area to a point one hundred miles out to sea. Attacks by Japanese flying bombs created additional hazards requiring Lieutenant Farrell to employ evasive tactics. His courage and determination in the face of enemy opposition combined with his skill and professional ability which made possible the successful accomplishment of this mission reflect great credit on himself and the Army Air Forces. Jim had a distinguished career in civilian life and was a popular member of the 73rd Bomb Group Association and the 500th Bomb Group Memorial Association.” Although not shy, my Dad was a private person and very humble. He was adamant about not having a funeral or memorial service. This is my little tribute to the man who inspired me with his strong work ethic, his positive attitude and unceasing optimism.

(R. Cookson-)

It has been my pleasure to make the acquaintance of Colonel James R. Farrell, who flew 36 accredited missions from Saipan to Japan in the Z Square 34, the "Frisco Nannie" while attached to the 882nd Squadron of the 500th Bomb Group.

Colonel Farrell has been kind enough to answer all of my many questions with clarity and definition that is truly appreciated. The colonel is extremely gracious, and equally humble when he speaks of his war time

experiences flying the B-29s over Japan.

Although the colonel said he may have met my Uncle Bob's A/C Major Robert Fitzgerald, he said he had not known him personally. My question had been whether an A/C with Major Fitzgerald's rank could refuse a promotion to H.Q. etc., so he could continue flying. Colonel Farrell said that Major Fitzgerald being promoted to Major in 1942 should have meant he would have come into the organization perhaps as a Squadron Commander or an Operations Officer, but that

he could have continued to fly as an A/C. Colonel Farrell refered me to the 881st Operations Officer Robert Goldsworthy who I have spoken to.

More on Major Goldsworthy later.

In answer to my question regarding the order for all B-29 crews to maintain radio silence on the missions from Saipan to Japan, Colonel Farrell responded that to his recollection, they "were only required to maintain radio silence on the way to the target.....

this was to help minimize their discovery by the Japanese."

For further clarification on radio-silence, Jim Bowman offered the following reasons for doing so.

The Japanese usually knew the B-29s were coming because they had radar posts in the Bonins and on other small islands,

but undisciplined chatter from the B-29s would make it easier for them. The Japanese could DF the transmissions and get accurate fixes or gain intelligence.

If the enemy could identify the call sign of the force leader, an English speaking Japanese could get on the same frequency and give false orders such as ordering a premature turn. Also, on the B-29s only one station can transmit on a given frequency at a time, so if two or more try to transmit simultaneously one will block the other, or they may block each other and no one will understand anything.

It was imperative to leave these frequencies open for leader commands, or emergency calls in case of ditchings.

To my inquiry about all crew members of a B-29 being asleep on the return trip to Saipan after a bombing mission over Japan, the colonel stated......."Yes. It did happen. With the plane on auto-pilot I do recall on my period of sleep, awakening to find the Co-pilot also asleep. We were all extremely fatigued by the time we left the target and would rotate between crew members periods of sleep."

Jim Bowman and I also discussed the above issue on crews falling asleep during the return to Saipan.

The crews would usually turn on the C-1 autopilot on the way home with course, altitude and speed all set, then they would take it easy....unless rough weather or a mechanical issue interfered. One of either the A/C or Co-pilot was supposed to stay awake, but as Colonel Farrell stated, sometimes both fell asleep.

It a very long, tiring and dangerous trip, and adrenalin makes you tired too. Jim referred to the following memoirs of a B-29 tail gunner flying out of Guam.

The TG said that once returning from a mission in perfectly clear skies, he saw another B-29 at the same altitude

traveling at a slightly higher speed approach from the right rear on an intercepting course. As the other B-29 came closer

the TG expected them to see the danger and change course. But, they didn't. They just kept coming. Finally, the TG got on the interphone and yelled to his A/C to dive, which he did just in time and they avoided a collision. The TG watched as the other plane flew on by, right on the same course, and off into the distance.

Obviously, the other crew had been asleep.

I was curious as to whether Colonel Farrell remembered anything specific about the first low level fire bombing raid of

Kobe on 16/17 March 1945 when Uncle Bob and the Fitzgerald crew were lost, but he said he didn't recall anything

special about this mission.

So I asked him as A/C what his feelings were when he first discovered during the first week of March, 1945, that General LeMay had ordered low-altitude, night, incendiary raids over Japan, without guns or ammuntion. Answering matter of factly, the Colonel replied that "most crews thought it would be a disaster,.....but, Ours not to question Why - Ours but to do or etc........"

I also asked the colonel if he and his crew de-pressurized their plane and went on oxygen before, during, and immediately after bombing missions at high altitude over Japan. Colonel Farrell replied that " we did both--selectively and on my decision."

Colonel Farrell also clarified the location of all airfields on Saipan and which planes or groups flew from these fields,

to my friend Jim Bowman and the group as follows:

Isley Field #1 &2. B-29s.

Kobler Field. ATC, plus a squadron of Marine C-46 transports.

East Field. Hdqrs. of the 7th AAF, which included B-24s, P-38s, P-47s, & P-61 night fighters.

North Field. Army ground forces, L-4 & L-5 Liaison planes.

The following story related by Colonel Farrell I found fascinating as well as extremely harrowing. To be "shot down" by one of your own propellers over the Pacific Ocean after successfully bombing Japan would have been the saddest of ironies.

This is the colonel's narrative of what occured:

"An engine shot out over Japan above 30,000 feet wouldn't feather. Knowing we couldn't make it back with a windmilling

prop, I decided to try to shake it loose by aggravating the situation.

Diving the bird past the red-line, when the prop-hub turned moulton red, I pulled out and gave the stick a sharp jolt which

caused the prop to come off, sailing straight forward for about 3 miles where it stopped and just hung in the air.

Motionless (other than it spinning) it held there until we caught up with it about 30 seconds later, and about a hundred yards to it's left.

At that point it arched right across the top of our bird almost exactly from the point it had left on our #3 engine."

(R.Cookson)

Colonel Farrell has been kind enough to answer all of my many questions with clarity and definition that is truly appreciated. The colonel is extremely gracious, and equally humble when he speaks of his war time

experiences flying the B-29s over Japan.

Although the colonel said he may have met my Uncle Bob's A/C Major Robert Fitzgerald, he said he had not known him personally. My question had been whether an A/C with Major Fitzgerald's rank could refuse a promotion to H.Q. etc., so he could continue flying. Colonel Farrell said that Major Fitzgerald being promoted to Major in 1942 should have meant he would have come into the organization perhaps as a Squadron Commander or an Operations Officer, but that

he could have continued to fly as an A/C. Colonel Farrell refered me to the 881st Operations Officer Robert Goldsworthy who I have spoken to.

More on Major Goldsworthy later.

In answer to my question regarding the order for all B-29 crews to maintain radio silence on the missions from Saipan to Japan, Colonel Farrell responded that to his recollection, they "were only required to maintain radio silence on the way to the target.....

this was to help minimize their discovery by the Japanese."

For further clarification on radio-silence, Jim Bowman offered the following reasons for doing so.

The Japanese usually knew the B-29s were coming because they had radar posts in the Bonins and on other small islands,

but undisciplined chatter from the B-29s would make it easier for them. The Japanese could DF the transmissions and get accurate fixes or gain intelligence.

If the enemy could identify the call sign of the force leader, an English speaking Japanese could get on the same frequency and give false orders such as ordering a premature turn. Also, on the B-29s only one station can transmit on a given frequency at a time, so if two or more try to transmit simultaneously one will block the other, or they may block each other and no one will understand anything.

It was imperative to leave these frequencies open for leader commands, or emergency calls in case of ditchings.

To my inquiry about all crew members of a B-29 being asleep on the return trip to Saipan after a bombing mission over Japan, the colonel stated......."Yes. It did happen. With the plane on auto-pilot I do recall on my period of sleep, awakening to find the Co-pilot also asleep. We were all extremely fatigued by the time we left the target and would rotate between crew members periods of sleep."

Jim Bowman and I also discussed the above issue on crews falling asleep during the return to Saipan.

The crews would usually turn on the C-1 autopilot on the way home with course, altitude and speed all set, then they would take it easy....unless rough weather or a mechanical issue interfered. One of either the A/C or Co-pilot was supposed to stay awake, but as Colonel Farrell stated, sometimes both fell asleep.

It a very long, tiring and dangerous trip, and adrenalin makes you tired too. Jim referred to the following memoirs of a B-29 tail gunner flying out of Guam.

The TG said that once returning from a mission in perfectly clear skies, he saw another B-29 at the same altitude

traveling at a slightly higher speed approach from the right rear on an intercepting course. As the other B-29 came closer

the TG expected them to see the danger and change course. But, they didn't. They just kept coming. Finally, the TG got on the interphone and yelled to his A/C to dive, which he did just in time and they avoided a collision. The TG watched as the other plane flew on by, right on the same course, and off into the distance.

Obviously, the other crew had been asleep.

I was curious as to whether Colonel Farrell remembered anything specific about the first low level fire bombing raid of

Kobe on 16/17 March 1945 when Uncle Bob and the Fitzgerald crew were lost, but he said he didn't recall anything

special about this mission.

So I asked him as A/C what his feelings were when he first discovered during the first week of March, 1945, that General LeMay had ordered low-altitude, night, incendiary raids over Japan, without guns or ammuntion. Answering matter of factly, the Colonel replied that "most crews thought it would be a disaster,.....but, Ours not to question Why - Ours but to do or etc........"

I also asked the colonel if he and his crew de-pressurized their plane and went on oxygen before, during, and immediately after bombing missions at high altitude over Japan. Colonel Farrell replied that " we did both--selectively and on my decision."

Colonel Farrell also clarified the location of all airfields on Saipan and which planes or groups flew from these fields,

to my friend Jim Bowman and the group as follows:

Isley Field #1 &2. B-29s.

Kobler Field. ATC, plus a squadron of Marine C-46 transports.

East Field. Hdqrs. of the 7th AAF, which included B-24s, P-38s, P-47s, & P-61 night fighters.

North Field. Army ground forces, L-4 & L-5 Liaison planes.

The following story related by Colonel Farrell I found fascinating as well as extremely harrowing. To be "shot down" by one of your own propellers over the Pacific Ocean after successfully bombing Japan would have been the saddest of ironies.

This is the colonel's narrative of what occured:

"An engine shot out over Japan above 30,000 feet wouldn't feather. Knowing we couldn't make it back with a windmilling

prop, I decided to try to shake it loose by aggravating the situation.

Diving the bird past the red-line, when the prop-hub turned moulton red, I pulled out and gave the stick a sharp jolt which

caused the prop to come off, sailing straight forward for about 3 miles where it stopped and just hung in the air.

Motionless (other than it spinning) it held there until we caught up with it about 30 seconds later, and about a hundred yards to it's left.

At that point it arched right across the top of our bird almost exactly from the point it had left on our #3 engine."

(R.Cookson)

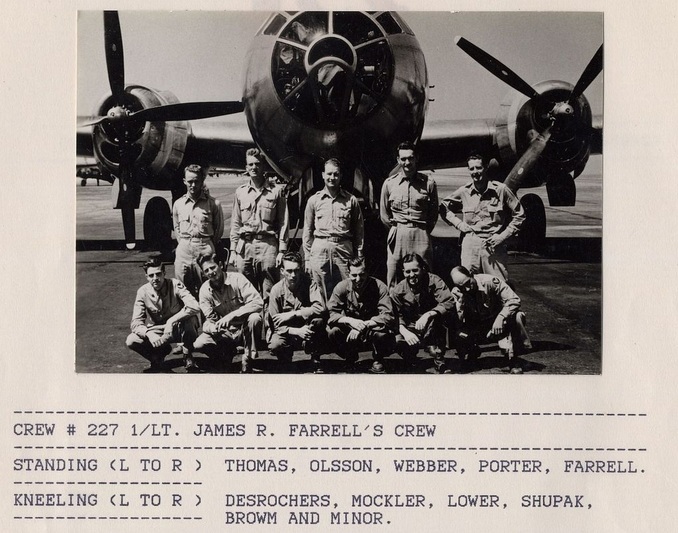

Farrell aircrew

Z-34 "Frisco Nannie" Crew

Crew changes of the "Frisco Nannie."

Officers:

Lt. Porter, Co-Pilot, was the first to be checked out as an A/C and was given his own crew, the former Gerwick crew, in January, 1945. Sadly, he was shot down on his first mission as A/C on 23 Jan 45. Lt. Betts was finally selected to replace Lt. Porter after James Farrell had eliminated two other candidates for the job.

Flight Engineer Thomas separated his shoulder at the staging area before the crew left Nebraska, and was replaced by Lt. Arterburn. A/C Farrell learned somewhat later that Arterburn was color-blind, but it did not affect his performance.

Enlisted:

A/C Farrell could not remember the circumstances that led to the replacement of Desrochers and Minor by

Sidney Long and Julius Atkins.

Officers:

Lt. Porter, Co-Pilot, was the first to be checked out as an A/C and was given his own crew, the former Gerwick crew, in January, 1945. Sadly, he was shot down on his first mission as A/C on 23 Jan 45. Lt. Betts was finally selected to replace Lt. Porter after James Farrell had eliminated two other candidates for the job.

Flight Engineer Thomas separated his shoulder at the staging area before the crew left Nebraska, and was replaced by Lt. Arterburn. A/C Farrell learned somewhat later that Arterburn was color-blind, but it did not affect his performance.

Enlisted:

A/C Farrell could not remember the circumstances that led to the replacement of Desrochers and Minor by

Sidney Long and Julius Atkins.

Left to Right,back row: Capt. G. Gilbert, A/C; Lt. D. Lundgren, pilot; Lt. L. Larson, bombardier; Lt. L. Pipkin, Navigator; MSgt. C. Harris, engineer.

Left to right, front row: SSgt. W. Kidda, radio; TSgt. J.Cooper, CFC; SSgt. J. Kolins, radar; SSgt. V. Sherwood, Left gunner; SSgt. C. Weber, Right gunner; SSgt. P. McCutcheon, Tail gunner.

The above photograph of the Gillert crew was provide to us by John Tiscornia, who discovered it in some papers after the death of his father. John's father served with General Patton in Europe and was highly decorated. We have since discovered that John's father had been good friends with Charles Weber of this crew.

Gillert and his crew arrived as replacements on Saipan and were assigned to the 882nd Squadron. Their first mission, and the only one they flew on the Z Square 34, "Frisco Nannie", was the incendiary raid on 13 March 1945. This crew survived the war.

Left to right, front row: SSgt. W. Kidda, radio; TSgt. J.Cooper, CFC; SSgt. J. Kolins, radar; SSgt. V. Sherwood, Left gunner; SSgt. C. Weber, Right gunner; SSgt. P. McCutcheon, Tail gunner.

The above photograph of the Gillert crew was provide to us by John Tiscornia, who discovered it in some papers after the death of his father. John's father served with General Patton in Europe and was highly decorated. We have since discovered that John's father had been good friends with Charles Weber of this crew.

Gillert and his crew arrived as replacements on Saipan and were assigned to the 882nd Squadron. Their first mission, and the only one they flew on the Z Square 34, "Frisco Nannie", was the incendiary raid on 13 March 1945. This crew survived the war.

Her nose art...

Z-34 nose art

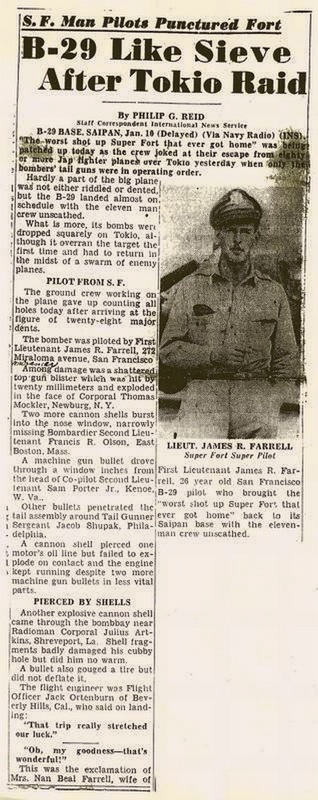

The newspaper article above was provided to us by A/C James Farrell. It describes in detail his bombing mission to

the infamous Target 357, the Nakajima Aircraft Engine factory in Musashino, Japan, near Tokyo on 9 January 1945.

We were able to determine that he was piloting Z Square 30, the "Constant Nymph", and bombed the target from approximately 30,000 feet with ten (10) 500 pound general purpose bombs.

A/C Farrell was in position 4 in a four plane formation. Unfortunately on his first pass, he had a bomb rack malfunction and

could not drop his payload. He made the unenviable decision to go around and try again, and on his second bomb run was able to drop his bombs on Tokyo.

Note of interest; Initially, two crews had to share a B-29 because of the lack of sufficient aircraft. One crew would be the primary crew, and the other the secondary crew for each plane. A/C Farrell has said that in his case, he and the other A/C "flipped a coin" to determine who would be the primary crew who would also get to name the plane.

James Farrell lost the coin flip, and his became the secondary crew flying the "Constant Nymph." Soon after he did

receive his own B-29 which he named the "Frisco Nannie," and flew it for the rest of the war.

the infamous Target 357, the Nakajima Aircraft Engine factory in Musashino, Japan, near Tokyo on 9 January 1945.

We were able to determine that he was piloting Z Square 30, the "Constant Nymph", and bombed the target from approximately 30,000 feet with ten (10) 500 pound general purpose bombs.

A/C Farrell was in position 4 in a four plane formation. Unfortunately on his first pass, he had a bomb rack malfunction and

could not drop his payload. He made the unenviable decision to go around and try again, and on his second bomb run was able to drop his bombs on Tokyo.

Note of interest; Initially, two crews had to share a B-29 because of the lack of sufficient aircraft. One crew would be the primary crew, and the other the secondary crew for each plane. A/C Farrell has said that in his case, he and the other A/C "flipped a coin" to determine who would be the primary crew who would also get to name the plane.

James Farrell lost the coin flip, and his became the secondary crew flying the "Constant Nymph." Soon after he did

receive his own B-29 which he named the "Frisco Nannie," and flew it for the rest of the war.

This is a letter from Col. Farrell written to the son of his tail gunner, Jake Shupak

(noted on pages 11 & 12 of the Col.'s Memoirs below)

(noted on pages 11 & 12 of the Col.'s Memoirs below)

| 10-25-2011_10 | |

| File Size: | 3044 kb |

| File Type: | 10-25-2011 10 |